|

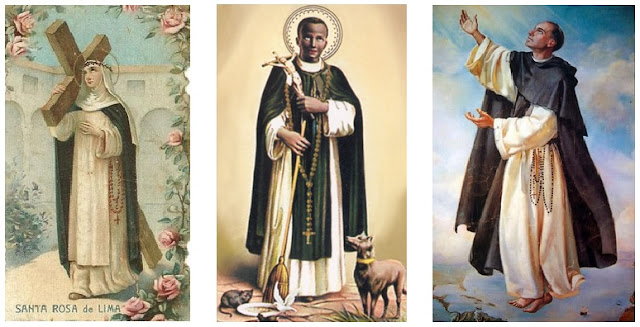

(Left to Right): St. Rose of Lima, St. Martin de Porres, and St. Juan Macias. |

In the heart of the Americas during the 16th and 17th centuries, three extraordinary persons rose to prominence for their deep love of God and service to others: St. Martin de Porres, St. Rose of Lima, and St. John Macias. Although distinct in their paths, each of them shared a commitment to compassion, humility, and relentless care for the marginalized. Their lives continue to inspire people around the world, offering timeless examples of faith in action.

St. Martin de Porres: The Humble Healer

Born in 1579 in Lima, Peru, St. Martin de Porres was the son of a Spanish nobleman and a freed African woman. Martin faced discrimination and poverty from a young age, shaping his deep empathy for those who were marginalized. Despite challenges, he found solace and purpose in the Dominican Order as a lay brother, where he dedicated his life to serving the sick and the poor.

Martin was known for his profound humility and tireless efforts to provide medical care to anyone in need. He set up an infirmary for humans and animals alike and cared for those with illnesses that others feared. Beyond his physical healing, Martin’s compassion radiated a powerful spiritual healing to all who encountered him. He became known for miraculous occurrences, such as bilocation and levitation, and his ability to communicate with animals. Canonized in 1962, St. Martin de Porres remains a model of racial harmony, humility, and mercy.

St. Rose of Lima: A Life of Penance and Devotion

St. Rose of Lima, born Isabel Flores de Oliva in 1586, was the first person born in the Americas to be canonized. Known for her remarkable beauty, Rose chose a life of severe penance and asceticism, rejecting societal pressures and devoting herself to God alone. Inspired by the suffering of Christ, Rose inflicted various penances upon herself, such as wearing a crown of thorns and living in a small hut in her family’s garden. Despite her harsh practices, she cultivated a deep inner peace and joy, dedicating her life to prayer and care for the poor.

Rose’s love for God overflowed into her love for her neighbors. She opened her family home to the poor and sick, caring for them tirelessly and bringing comfort to those in need. Her mystical experiences, intense piety, and unwavering compassion for the suffering inspired many, and in 1671, she was declared a saint. Today, St. Rose of Lima is recognized as the patroness of the Americas and the Philippines, embodying a life of sacrifice, devotion, and love.

St. John Macias: The Guardian of the Poor

St. John Macias, born in Spain in 1585, moved to Peru as a young man after feeling a deep calling to serve God. He entered the Dominican Order as a lay brother, dedicating his life to humble service and prayer. Known for his simplicity and sincerity, John devoted his days to helping the poor and hungry, often with miraculous results.

John had a special gift of charity, distributing food and alms to the needy of Lima and advocating for the most destitute in his community. Although he never held a prominent position, he became known for his sanctity, performing miracles like bilocation and healing through his prayers. Canonized in 1975, St. John Macias is remembered for his unwavering dedication to the impoverished, humility, and constant prayer.

A Shared Legacy

While each saint had unique gifts and paths, Martin de Porres, Rose of Lima, and John Macias shared a profound commitment to God and to the well-being of others. They remind us that holiness is often found in humble acts of kindness, in caring for the marginalized, and in being a voice for those who have none. Their lives invite us to look beyond ourselves and, through faith and compassion, to work for a world of greater justice, peace, and love.

The friendship among these saints was primarily one of shared spiritual ideals, with each one drawing strength and inspiration from the others' example. Their legacies as friends in faith and Dominican spirituality continue to resonate, reminding us of the power of community in pursuing holiness and compassion.

%20(1).jpeg)

.jpeg)